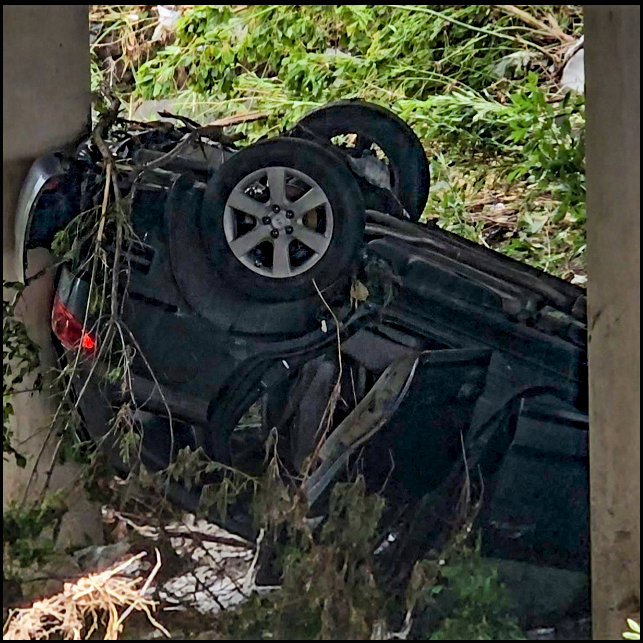

Hurricane season has gotten underway throughout recent weeks with Hurricane Ida, a major hurricane bringing devastation to the states of Louisiana and Mississippi. Torrential rain, wind speeds reaching over 100 mph and even tornadoes were spotted from the Gulf states of Louisiana and Mississippi and even as far as New England.

Kurt Van Speybroeck, a meteorologist with the National Weather Service, said the devastation in the southern states was caused by a multitude of weather events caused by the hurricane, causing electricity outages.

“What we saw was a lot of rain, quite a bit of wind reports, a lot of power outages and downed trees, some flooding of homes and it was a major hurricane so you would expect that the damage would match with a Category 4 hurricane.”

While the damage was severe in Louisiana, it reached further into Mississippi, according to Van Speybroeck.

“The extent of the damage did reach all the way up into the Gulf Coast states. It reached all the way up to Mississippi, right towards the Jackson area with a lot of tree damage and downed trees in central and northern Mississippi.”

Hurricane Ida completely dissipated on Sept. 4, leaving behind 26 dead in Louisiana, according to the Louisiana Department of Health. Over 40 were confirmed dead, according to the Associated Press. The damage cost in Mississippi and Louisiana is estimated to be between 27 and 40 million dollars, according to the website CoreLogic.com.

On Sept. 9, the National Hurricane Center began monitoring a disturbance in the Bay of Campeche. Eventually, this disturbance became a Category 1 hurricane that struck the coasts of Texas and Louisiana. Although it was given the weakest rating on the Saffir Simpson Scale, it did not leave the affected areas unscathed.

“The main impact that we saw was localized flooding, isolated flooding in Southeast Texas. Generally from Matagorda Bay up to the south and southeast side of Houston. We did see quite a bit of coastal erosion and wave action type damage. Some wind damage on the immediate coast,” said Van Speybroeck.

Van Speybroeck said many power lines have been downed due to falling trees.

However, Hurricane Nicholas was problematic as it barely hung onto its status as a hurricane.

“Nicholas was briefly a hurricane, there were just a few observations that said that there was hurricane force winds for a short period of time so it was right on the border of strong tropical storm and hurricane,” said Van Speybroeck.

As Nicholas moved east, it weakened to a tropical depression. Despite being less than a hurricane, it moved toward Louisiana and affected areas that were previously hit by Hurricane Ida.

“The heaviest rain fell in Louisiana. It was over Lake Charles and then transitioned to the area where Ida went,” Van Speybroeck said.

At press time, the National Hurricane Center has posted an advisory on Tropical Depression Nicholas, stating it was nearly stationary over the gulf states and bringing a risk of flash flooding across parts of the central gulf coast region.

While both Hurricane Ida and Nicholas were completely different in terms of strength of wind speeds, they still brought a dangerous part that every tropical system includes; the storm surge.

Stephen Kallenberg, earth science and environmental science faculty for Dallas College Richland Campus, explained what a storm surge is.

“What a hurricane is at the very very center, the eye of the hurricane, there is a very low pressure, it’s a deep low pressure. So the air is actually being lifted so the air is going upwards and the air in the hurricane in the center is so strong, that it’s actually pulling the water up. And so there’s this bulge of water near the eyewall basically and it’s around the hurricane so this bulge of water is kinda like just a slow moving tidal wave in a sense that’s just following along with the storm,” said Kallenberg.

Hurricane season begins in June and ends in November but it may begin earlier or end later. Kallenberg believes that more hurricanes are a possibility.

“For sure. The hurricane season doesn’t end until November 30th so there’s still plenty of time,” said Kallenberg.

At press time, three areas of the Atlantic Ocean are being monitored by the National Hurricane Center for possible development of tropical systems. Kallenberg said many of these could fully develop within the span of days.

“It could still strengthen, there’s enough warmth in the Atlantic. It could turn into a hurricane so that’s possible,” Kallenberg said.

NOAA has stated the 2021 Atlantic Hurricane season to have a 60% chance of being an above-average hurricane season, Kallenberg agrees with the notion.

“On average, we get about 14.2 named storms, 7.2 hurricanes, about 3.2 major hurricanes. Where we stand right now, we got 14 named storms and we’re likely going to add two more by the end of the week so we’ll probably be at 16 so that’s slightly above average,” said Kallenberg.

As more tropical storms may form throughout the upcoming weeks, Van Speybroeck advises people to responsibly be aware of any official warnings and to be updated on the latest information about hurricanes, especially as social media may cause confusion amongst official messages and opinions of those on the platforms.

“What we suggest people do is for people to follow information from the National Hurricane Center and now with social media and all the different YouTube channels and everybody having a forecast or an opinion, sometimes it’s hard to see the official message so that’s why we point everybody to the official messages that come out from the National Hurricane Center,” said Van Speybroeck.

Local weather offices are helpful as they will also provide information about inclement weather affecting the area, even if it’s about a hurricane.

“We have them everywhere from Brownsville through the upper coast and all the way to Florida and there are 132 weather offices that deal with different hazards, Van Speybroeck said.”