Journalism, at its core, has always been a balance of ideals and economics.

News organizations need funding, and with billionaires at the helm, the tension between public service and private interest has become more pronounced.

When powerful owners influence major editorial decisions, particularly by opting out of politically charged endorsements, it raises concerns about the true drivers behind journalistic choices.

Are decisions made in the public’s interest, or do they serve to protect business interests and shield owners from potential political repercussions?

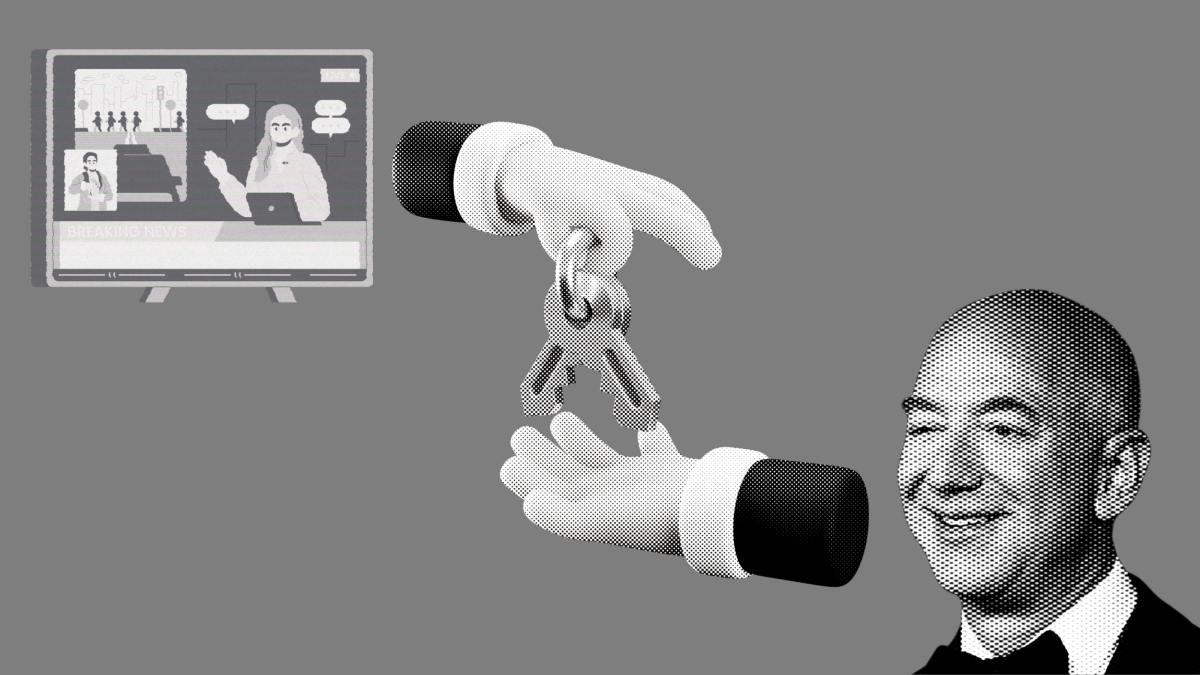

The recent decision by The Washington Post, following its owner’s denial of publication, to forgo endorsing Vice President Kamala Harris in her presidential run has stirred the media world and has spotlighted an unsettling question: Who truly controls journalism?

This shift, mirrored by the Los Angeles Times and supported by their respective owners, Jeff Bezos and Dr. Patrick Soon-Shiong, portrays a more alarming trend where powerful private interests can shape the direction of supposedly independent media.

The Washington Post’s move is part of an ongoing debate about the role of the press in a fractured political environment.

While leadership framed the withdrawal as a step toward objective reporting, the timing suggests a more complex narrative.

At a moment when the stakes of democratic governance are higher than ever, pulling back from endorsements reflects more than prudence; it signals a reluctance to take a stand that could risk alienating portions of an audience or provoking political pressure.

The influence of ownership over journalism is not a new dilemma.

Historically, media moguls have wielded their power to sway public perception, and the promise of independent journalism has always depended on an editorial firewall. Yet, when influential newspapers like The Washington Post choose to step back from endorsing candidates, it casts a shadow over whether ownership interests are compromising editorial independence, subtly or overtly.

Critics of the Post’s decision, including notable resignations and dissenting staff, argue that avoiding endorsements weakens the role of the press as a proactive force in democracy.

The underlying message is troubling: If billionaires decide that editorial courage is too risky for their bottom line, how free is the press?

Journalism must resist the temptation to retreat into a sterile form of neutrality, as doing so allows power structures to remain unchallenged, unchecked and comfortably out of the limelight.

The Los Angeles Times’ similar decision under Soon-Shiong’s ownership emphasizes this dilemma.

It creates a serious reflection on the responsibilities of media giants and how they navigate their dual roles as stewards of public information and guardians of private business interests.

If media owners, swayed by commercial considerations or apprehensive of political repercussions, start pulling back from practices like candidate endorsements, the press risks becoming less of a civic beacon and more of a participant in public debate.

This shift has implications for the future of independent journalism and democracy itself.

The Richland Chronicle urges both The Washington Post and the Los Angeles Times, and any media organization caught in similar quandaries, to recognize that journalism’s greatest asset is its willingness to inform, challenge and, when necessary, provoke.

Ownership influence should never dilute that mission, for the press must always belong to the public it serves, not just the individuals who hold its reins.